Spotted Lanternfly, an Invasive Pest Threatening Grapes and Other Crops, Found in Ithaca, NY

|

|

Spotted lanternfly adult. Photo by Michael Houtz. |

A population of spotted lanternfly (SLF) has been found in Ithaca, NY, just off the Cornell University campus.

They were found on their favorite host plant, another invasive species, tree of heaven (Ailanthus altissima). However, SLF also feeds on many other trees and plants, which, unfortunately, includes grapevines. With New York State’s important Finger Lakes grape-growing region and wine industries so close to Ithaca, state agencies and researchers are particularly concerned about this pest’s impact in the region.

SLF is not a fly, but rather a large planthopper. Adults are about an inch long. SLF does not bite or sting and is not a threat to people, pets, or livestock. For most New Yorkers, it will be no more than a nuisance pest. Nymphal and adult SLF have piercing-sucking mouthparts that drill into plant phloem. SLF’s excrement—a sappy liquid called honeydew—makes things sticky and becomes a breeding ground for sooty mold, an annoying black fungal growth.

While SLF is native to Asia, it was first found in the U.S. in Pennsylvania. As the pest has begun to spread to neighboring states, knowledge and experience from Pennsylvania’s SLF researchers and specialists has been benefiting New York. Pennsylvania agriculture experienced losses of entire grapevine plants in some vineyards, and their economists estimate a potential combined annual loss to their state of $324 million and 1,665 jobs.

Because SLF is a significant agricultural pest, research is underway even now, as Cornell investigates biological control and other management options. The goal is to develop a holistic integrated pest management (IPM) strategy to combat spotted lanternfly, incorporating a variety of research-driven techniques to supplement the use of pesticides wherever possible. This will minimize the downsides of a pesticide-first strategy, which include detrimental effects on humans, pets, livestock, and other non-target organisms, as well as the development of pesticide resistance (and resulting loss of effectiveness) in the target pest.

The New York State IPM Program (NYSIPM) and the Northeastern IPM Center, in conjunction with the state’s Department of Agriculture and Markets and Department of Environmental Conservation, have been preparing for SLF’s potential arrival here for the last few years. In that time, we’ve developed educational resources to help recognize this insect and prevent its spread. Partnering with affected states, we’ve maintained a map tracking its spread and quarantines across the Mid-Atlantic and Northeast region.

To properly identify spotted lanternfly and understand its life cycle, its host plants, and how to monitor and manage it, visit:

“What Should I Do?”

If you think you see a spotted lanternfly, report it to New York State Department of Agriculture and Markets using the Spotted Lanternfly Public Report.

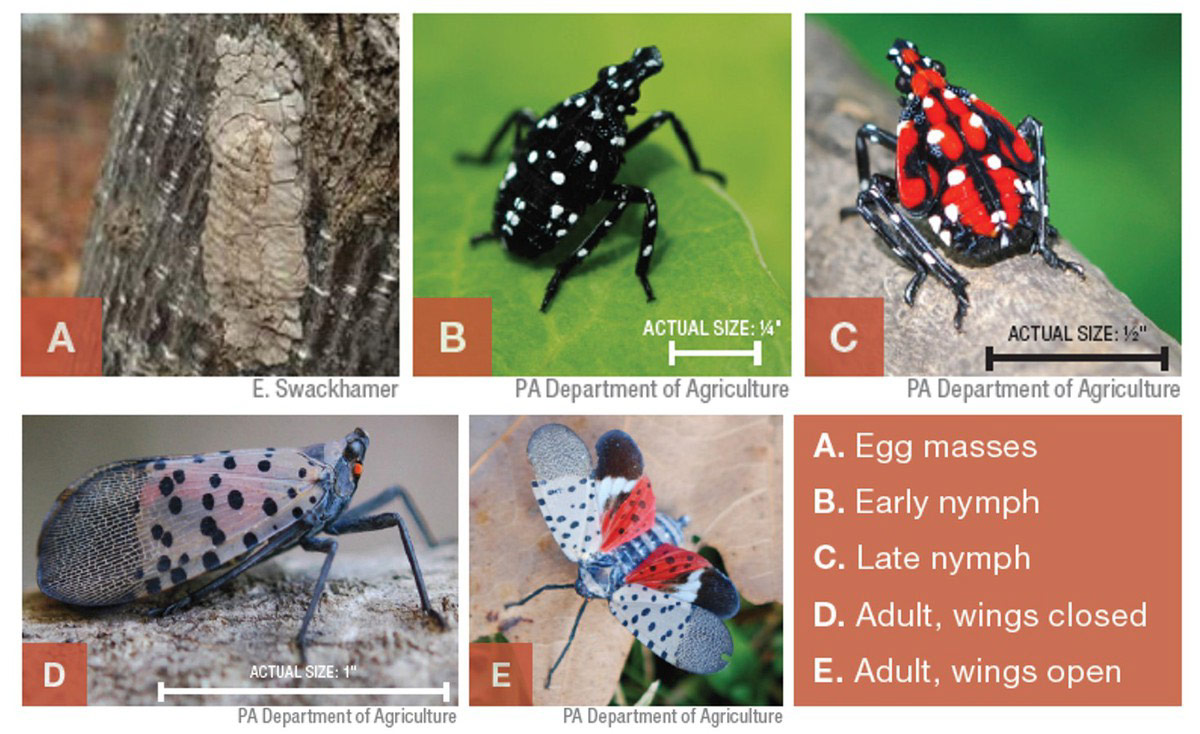

Check out the SLF life cycle, below, so you’ll know what to look for. From fall through spring, look for egg masses. Some resources on egg masses:

- Identifying Spotted Lanternfly Egg Masses (PDF)

- What Should You Do with Spotted Lanternfly Egg Masses?

- How to Remove Spotted Lanternfly Eggs

In late spring and early summer, look for the nymph stages. In late summer through fall, look for adults.

Don’t transport this pest. Individual and commercial travelers alike should be aware that there’s significant potential to unknowingly spread this insect to new areas. Adult SLF can end up in vehicles. Egg masses can be laid on virtually anything and can be easily overlooked. Inspect anything that you load into your vehicle. Consult the NYSIPM checklist.

Keep up with the latest news on the spread of SLF and other pest management concerns by bookmarking the NYSIPM blog, and following us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. You can find the Northeastern IPM Center on Facebook and Twitter.

Frequently Used Terms

Biological control: A strategy for managing pests that focuses on the introduction of exotic natural enemies, the application of predators, parasitoids, and microorganisms as biopesticides, and the manipulation of the environment to enhance natural enemy populations. (Source: Natural Enemies: An Introduction to Biological Control)

Integrated pest management (IPM): A science-based approach to dealing with pests that provides economic, environmental, and human-health benefits. While IPM is not opposed to traditional chemical pesticides, it encourages the use of effective alternatives where possible.

Invasive species (or invasive pest): An organism that causes ecological and/or economic harm in an environment where it is not native. Their introduction can sometimes be the result of human activity, and they are often more challenging to manage in non-native environments because of the lack of natural enemies that are present in their native habitats.

Nymph: An immature form of some insects that precedes a more developed immature form or the final adult stage. The insect’s appearance may change significantly between stages.

Phloem: The portion of living tissue in vascular plants that transports sugars, proteins, and other organic molecules. Pests like SLF bore into the phloem to consume these nourishing substances, often to the detriment of the host plant.

Planthopper: Any insect in the infraorder Fulgoromorpha, in the suborder Auchenorrhyncha, and exceeding 12,500 described species worldwide, as contrasted with flies (order Diptera), which include about 12,000 species. (Source: Wikipedia)

In practical terms, planthoppers differ from flies primarily in how they get around. Flies, as the term implies, tend to be capable flyers. While planthoppers can fly to some extent, they mostly walk or hop. Some planthoppers, like SLF, are colloquially referred to as flies, but they are not true flies.